The story begins with the 易經 [I Ching] I pilfered from my mother. Known as the Classic of Changes, this ancient Chinese divination manual has survived centuries of 變 [change] through numerous editions and has now been re-consolidated into a mass-market, decipherable text that rests on my bookshelf. The back cover modestly declares its worthlessness, only a few yuan to perform a 卜卦 [occultic ritual] and know your future. The dusty texture, mildly tinted pages, and the distinct smell of oxidised paper juxtapose its forbidden existence as it sits among other books, hinting at its possibly dubious and unethical origin.

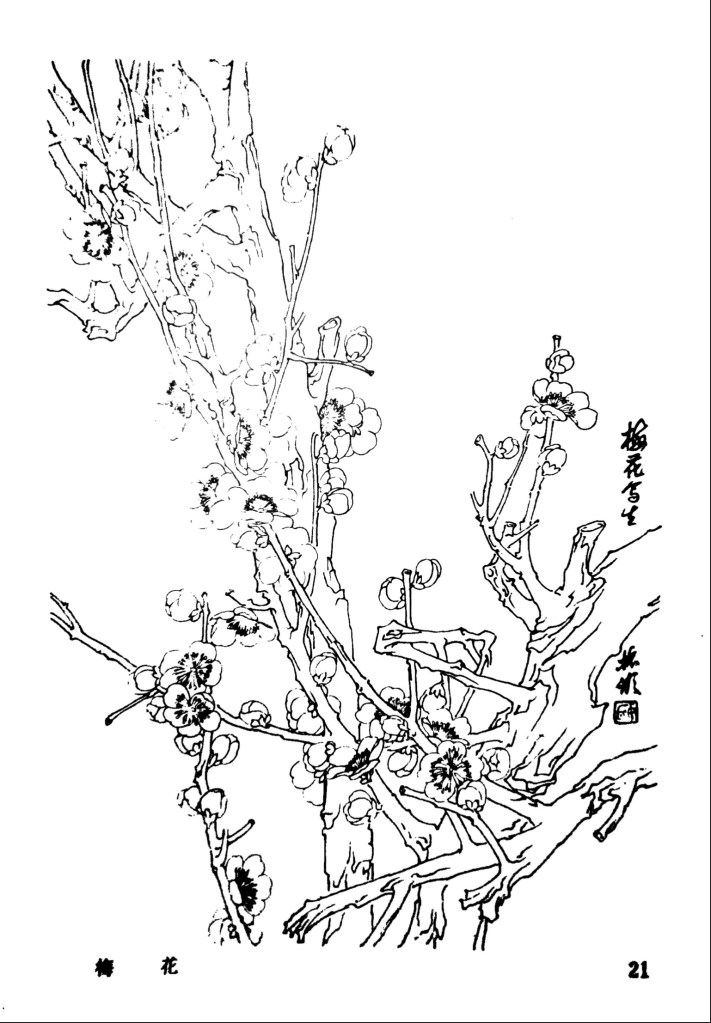

The rite of book stealing doesn’t really stop there. Guilty pleasure sustained as I appropriated the acquisition to expand my collection. Oracle nestled beside meticulous floral illustrations from 白描花卉技法 [Bai Miao Line Drawing Techniques of Flowers], another gem that I had carefully handpicked from my parents’ garden of knowledge. And when I finally confessed to my mother, she chuckled, only to reveal a bigger conspiracy: when she was young, she too had stolen books from her parents and grandparents, meaning that her cabinet of books was nothing more than a compilation of stolen treasures from generations past.

一代接一代的偷竊,在某種規律下竟然形成了正統的傳承。Generations of theft, somehow formulated a system and hence an official inheritance.

These books don’t even serve as a textual reference. They are barely read through, yet 我(們) [I/we] place so much emphasis on the ownership of this mythical, historical knowledge that is never assimilated. Despite being reasonably maintained, the meanings behind each word continue to deteriorate and render themselves as display objects. They are not meant to be read yet when placed together with other stolen artefacts, they become a collection of paper concepts that generations within my family hold and pass on. But if the stolen book’s original purpose becomes as irrelevant as the dust gathered on my shelf, what exactly has it evolved into? Is it now a superfluous matter that we shall deal with?

***

飢不可食 寒不可衣 [can’t feed the hunger, can’t warm the cold] – Superfluous matters are commonly described as non-useful, unnecessary, excessive, almost as futile as ornamentation. Yet ownership of such objects has long been a marker of one’s elite social status. In 長物志 [Treatise on Superfluous Things], everyday objects such as paintings, flowers, and furniture of certain materials, are meticulously documented and praised as signs of 雅 [elegance] and 入品 [in-trend]. While some are classified as more cultured and distinguished, the commentary reflects how “invention of taste”1 emerged as poets, nobles, and governors in ancient China consciously collected to differentiate themselves from the common. Ironically, what was considered superfluous in the past was also an essential lifestyle. As we delve deeper into the Treatise, we see that though the objects embodied luxury and elegance, they maintained a certain functionality. What rendered them superfluous though, was the underlying ideologies of being and living that they conveyed. With such sentiments, people no longer interacted with these objects for their made purposes. They are instead contextualised far beyond the material.

Engaging with superfluousity allows us to imply layers of imagination into the real world. In Arranging Things: A Rhetoric of Object Placement, Leonard Koren discusses how our senses construct an assumption of realness: we interpret through an exchange of light and shadow, perspective, and more importantly, observing and interacting with time. In doing so, we often forget that in reality, these are all driven by an imaginary mentality — one that diverges from ideal 純觀察 [pure observation]2. As we interpret objects in an abstract manner, their fundamental nature may become incomprehensible or even irrelevant. Yet what constitutes a relatable, ideal pure observation? Is it possible to intervene without subjectivity and, can we ever purposefully engage with the fantastical, false, and incomprehensible sides of still life?

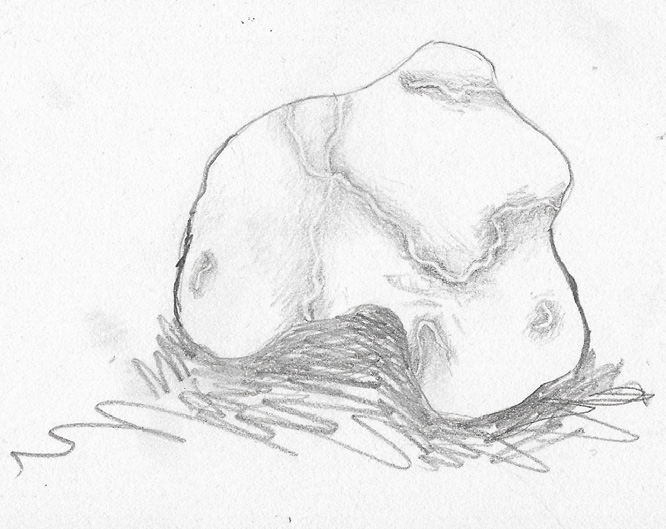

醜石不是一般的頑石,當然不能去做牆、做台階,不能去雕刻、捶布。它不是做這些小玩意兒的,所以常常就遭到一般世俗的譏諷。4 – 《諸神充滿》賈平凹

Ugly Rock is not a regular, stubborn stone, of course it cannot be used to build walls, stairs, nor can it be carved or used to wash clothes. It is not made for small gadgets and therefore always being satirised by the world. — Full of Gods, Jia Pingwa

Superfluousness manifests between the blurring lines of forms and matter, similar to how we seek aesthetics in “ugliness”. In 醜石 [Ugly Rock], an astronomer described to author Jia Pingwa the beauty of an asteroid beyond popular perception. He suggested that such objects are deemed superfluous only because they are mismatched, misused, misunderstood, or incompatible with the familiar. And what if the true purpose of certain objects, ideas, or existence becomes clear only when they appear irrelevant? By 褪去 [shedding] and forgetting about the permanence of thingness — its quality of being one thing rather than the other — we open ourselves to informative non-things that are “relevant only fleetingly”4. Superfluousity exists beyond objects’ secular presence, defined not by their materiality and functionality, but rather by their loose yet essential relationship with the viewer, user, and owner. In other words, the ambiguous matter becomes a transcription that allows us to untangle the 藕斷絲連 [fibrous remains of a broken lotus root] between humans, happenings, and the object.

Perhaps the existence of superfluous matters also serves to contain our inappropriate, overabundant thoughts. In an 1891 letter to a young man, Bernulf Clegg, Oscar Wilde wrote: “Art is useless because [of] its aim to simply create a mood. It is not meant to instruct, or to influence action in any way… A work of art is useless as a flower is useless.”5 If we return to the story of stolen books, we see how abundance and uselessness similarly build upon our emotional connections with the object. The I Ching no longer serves as a source of divination truth but a flavour of the past—it fails to exist as a book for reading, yet retains a materialised ideology that speaks about the continuity of lived experiences that my family shares, much like how artefacts displayed in museums demonstrate material culture extracted from their original context.

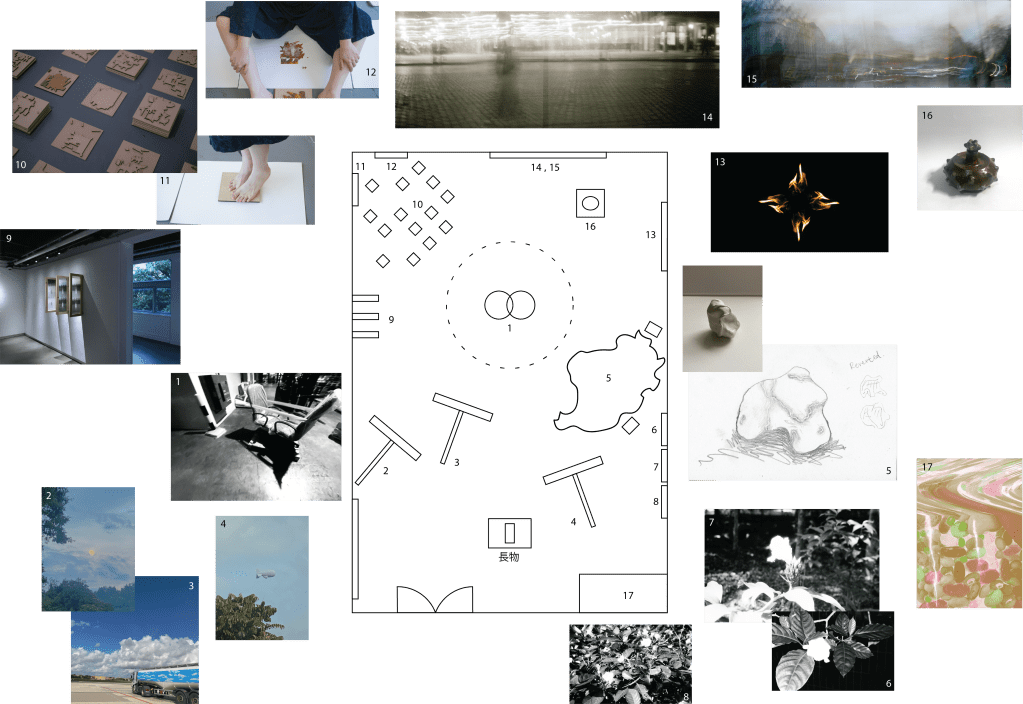

This book, Superfluous Matters, documents objects in forms of poetry and prose, all superfluous with the ambiguous thoughts they contain. As an extension of 新神話 [New Myth], the writings continue to contemplate self-reconfiguration through captured moments, indescribable feelings, and thoughts on the world. Two Chairs ventures into the intimacy of two chairs, understanding togetherness through the bilateral, mutual, and peripheral; Wishbone captures kinship and growth through a familiar bone broth recipe; Kungfu Teaware recalls friendship and a joyful afternoon at a tea bar; Ballad of Stars reflects on night thoughts, and Wildflowers yearns to capture sighs and lamentations… We conclude with a dystopian vision of a distanced home in Fish Eye. Such superfluous, ambiguous, and 不可描述 [indescriptive] feelings unfold like deconstructing an unstable moment and reshaping it into a book that assimilates the experience.

Ultimately, writing about superfluous matters itself becomes an ambiguous, superfluous object. Foreign terms with 似是而非 [seemingly] translations that over-complicate the reading experience. The written text vaguely captures the notion of how I write about things instead of what superfluous matters essentially are. It does now describe how objects behave as I see and speak about them. To once again re-engage with the fundamentals of superfluousity in Treatise: if a superfluous matter is reconciled as a leftover, then aren’t we all superfluous beings unable to adapt to reality? Perhaps this 突兀 [awkward] collection of words, objects, and worlds, seeks to unearth and manifest our own ambiguous identities, thoughts, and relationships.

- Clunas, Craig. 2004. Superfluous Things: Material Culture and Social Status in Early Modern China. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, P.171. ↩︎

- Koren, Leonard. 2020. Arranging Things A Rhetoric of Object Placement. Taipei: Flâneur Culture Lab, P. 8-9. ↩︎

- Jia, Pingwa. 2021. Zhu Shen Chong Man. Beijing: Beijing United Publishing Co., Ltd, P. 116. ↩︎

- Han, Byung Chul. 2022. Non-things: Upheaval in the Lifeworld. Cambridge: Polity Press, P.2. ↩︎

- Wilde, Oscar. 1891. “Art is useless because…”. Letters of Note. 4 Jan, 2010. https://lettersofnote.com/2010/01/04/art-is-useless-because/ ↩︎